Okay, I know it’s been three weeks since my last post. I’m on holiday, my laptop decided not to boot, and I didn’t have the recovery tools on hand so it took me a few days and much nail-biting to fix it. Anyway, I’m finally able to access my scribblings again, so here’s a somewhat lengthy review of The Hobbit trilogy I was working on. I wanted to write more, but it was already a bit wordy for a review, so if you ever want to know my thoughts about something specific just ask. And barring further laptop problems, I’ll try to have another post up next week before resuming my once-per-fortnight plan. Anyway…

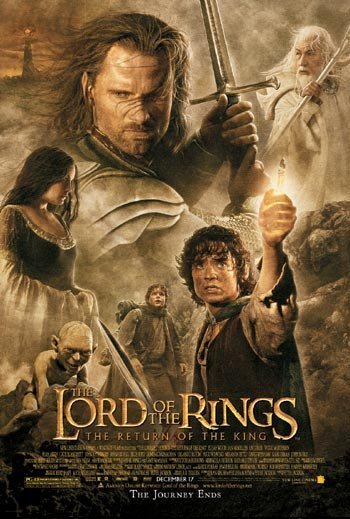

When Peter Jackson made film adaptations of Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings novels back in 2001-2003, it changed New Zealand’s whole reputation. Before those films, New Zealand was barely on the radar for most foreigners, except perhaps if they were rugby fans and knew of the All Blacks. After The Lord of the Rings, however, most of the world recognised New Zealand as “that place where Lord of the Rings was made,” with all the rolling landscapes and stunning vistas. It also did wonders for New Zealand’s tourism industry. The NZ tourism website remarks that in a 2004 survey, “One per cent of visitors said that The Lord of the Rings was their main or only reason for visiting. This one per cent related to approximately NZ$32.8m in spend.”

The Hobbit had a lot to live up to, then. Peter Jackson returning to the universe that made him and New Zealand famous? Regardless of the fact that The Hobbit is a much lesser story in scope than the trilogy that follows it, there was a lot of hype for Peter Jackson’s film adaptation. And I don’t think the film would have lived up to that hype if he’d just made a direct adaptation of the source material. As controversial as some of his additions were, they made a relatively humble story into a multi-film franchise that kept viewers coming back over three consecutive years. By pulling in plot elements from Tolkien’s other works (namely the Silmarillion), Peter Jackson created a trilogy that even challenged The Lord of the Rings for its massive success. In fact, the Hobbit trilogy grossed just $5 million less worldwide than The Lord of the Rings‘ US$2.9 billion – and it’s still in the cinemas, so there’s time yet.

But that’s all economics and politics. Were the movies actually good?

One of the things that has always drawn me to Tolkien’s works – and Peter Jackson’s associated films – is the clear depiction of good and evil. Middle Earth has always been about the fight between good and evil; the clash of light and darkness. For much of the Hobbit trilogy we see humans and dwarves and elves at each other’s throats and shifting alliances, yet we know that when the orcs turn up everyone will be fighting them instead, because they are the unquestionable evil that must be stopped.

It’s no secret that Tolkien was a Christian, so perhaps it’s no surprise that his fantasy works draw heavily from the biblical account of our own world’s creation. In particular, the genesis of Middle Earth almost directly mirrors the genesis of Earth. Stephen Colbert drew the parallels most clearly when he jocosely pointed out the differences between devils and balrogs:

Now, devils and Balrogs are totally different. Devils are angels who refused to serve God, and instead followed Satan into Hell. Balrogs are Maiar who refused to serve Eru, and instead followed Morgoth into Thangorodrim.

By that comparison, Gandalf (a Maiar) is the closest thing to an angel in Middle Earth. And he combats the evil works of Sauron (a fallen Maiar). Angels fighting demons, then. Granted, it’s not a clear parallel, but Tolkien was the guy who criticised his friend C. S. Lewis’ Narnia books for being theologically heavy-handed with their Christian themes (reference: here, page 2).

Regardless, both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings are rife with Christian themes. For instance, just as Bilbo seemed an unlikely choice for the Company’s quest so too does God often choose unlikely individuals to fulfil his grand plans. Another related theme is touched on by Gandalf when he says:

Saruman believes it is only great power that can hold evil in check, but that is not what I have found. I found it is the small everyday deeds of ordinary folk that keep the darkness at bay. Small acts of kindness and love.

Similarly, God came into our world not as a conquering king but as a humble carpenter whose selfless acts of kindness and love rid Satan from the hearts of millions.

There are many other themes explored throughout the trilogy, too. Themes of love (both romantic and familial variants); greed and the corruption it breeds; friendship across social standings and tested by fire (literally, in some cases); finding identity and a sense of belonging to a location or culture; the fine line between righteous honour and conceited pride; and, perhaps most distinctly, the unthinkable consequences that a seemingly-noble quest may carry for those around you.

Since this is a review of The Hobbit films – says so in the title – I should probably include some traditional review jazz here too. I’m more interested in analysing the lasting impression it leaves than the trilogy itself, but suffice to say, each film competently displayed the level of all-round polish that we’ve come to expect of big-budget movies. In fact, it’s quite probable that more work went into these films than the original Lord of the Rings ones. And it shows.

Smaug is simply unforgettable, both as a character and as an unspoken threat looming over the rest of the characters. The special effects work on the dragon himself is top-notch, and Benedict Cumberbatch brings life (and death, lots of death) to the character like no other. Ian McKellen as Gandalf and Orlando Bloom as Legolas… These guys are old hands at this, and they bring their best game to the table once more. Despite being shoehorned into the narrative, Legolas is as resourceful as ever with his bow and the environment, and his screen-time during action scenes was always entertaining. The new blood – Martin Freeman as Bilbo, Richard Armitage as Thorin, Sylvester McCoy as Radagast, Luke Evans as Bard, Evangeline Lilly as Tauriel, Lee Pace as Thranduil, and all the dwarves among others – they all do a fine job of bring their characters to life. I don’t know what could possibly have possessed Tolkien to write so many dwarves as main characters, but they were each portrayed in a unique way even if I still can’t remember all their names. In the third film, Laketown advisor Alfrid’s frequent appearances (and convenient disappearances) were also a constant source of amusement.

The musical score this time around isn’t quite as memorable as that of The Lord of the Rings, but maybe it’ll just take a bit of time to grow on me. The Shire’s theme is back of course, and sounds as awesome as ever. There’s also distinct themes for Laketown, Smaug, the company of dwarves, and the line of Durin that I noticed, each appropriately upbeat or stirring in their own way.

Like Peter Jackson’s first trilogy set in Middle Earth, The Hobbit is an adventure. Its pacing stumbles at times, but I would nonetheless describe it as a wild ride that belongs on every fantasy aficionado’s “list of movies to watch before I die” (come on, we all have one of them, don’t we?). To assert that any singular message should be derived from the films would be to chasten the freedom of interpretation implicit in all art, so here’s what the trilogy meant to me: no evil is so great that it can’t be overcome with a little courage and a lot of perseverance.

My parting thought: really, Tolkien? Thirteen dwarves? That’s just too many characters.